Scoping Review

Applied Theatre and Drama in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Scoping Review

Bronte Johnston1, Hartley Jafine1

Published online: July 6, 2022

1McMaster University

Corresponding Author: Bronte Johnston, email: johnsb11@mcmaster.ca

DOI: 10.26443/mjm.v20i2.930

Abstract

Background: Thematic arts have been integrated throughout various undergraduate medical education programs to improve students’ clinical skills, knowledge, and behaviours to train clinically competent physicians. Applied theatre and drama use theatrical performances and exercises respectively to guide education. Several medical schools across Canada and the United States have incorporated applied theatre and drama within their curriculums, but there is currently no compilation of these initiatives.

Methods: Using Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework for scoping reviews, the two authors searched journal databases for articles pertaining to theatre or drama activities being used in undergraduate medical education in Canada and the United States. Search terms revolved around applied theatre and undergraduate medical education. Twenty articles were read in full, 14 were included in this review. The articles were subjected to content analysis to understand how the studies connected with the CanMEDS framework, allowing to understand the impacts and merits of applied theatre and drama in undergraduate medical education.

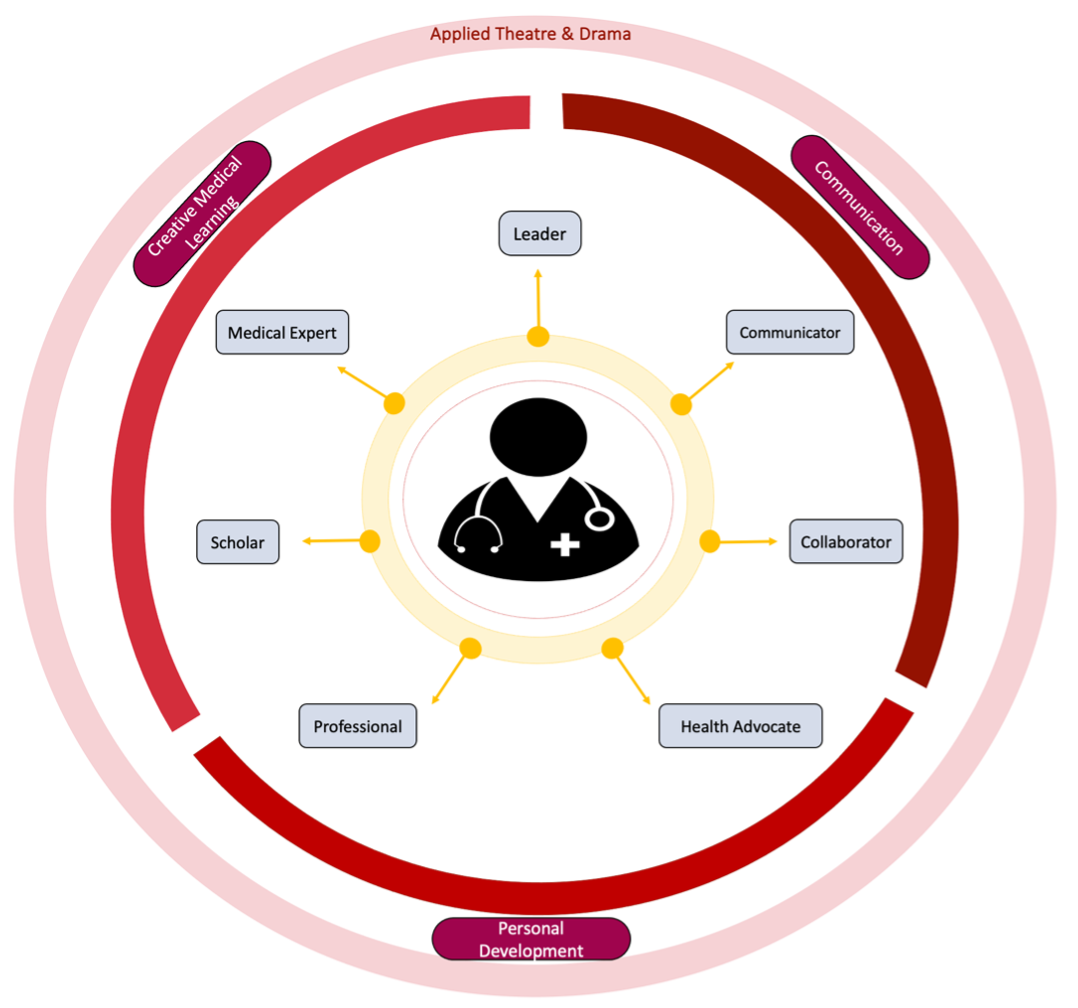

Results: Content analyses generated three categories for how theatre and drama can help medical faculties improve their students’ communication skills, integrate creative medical learning, and aid professional development. These three categories touched upon all seven aspects of the CanMEDS framework, indicating the value of drama being included in the current framework for medical education.

Conclusion : This scoping review illustrates the intersections between thematic arts and undergraduate medical education by highlighting how applied theatre or drama activities connect to the entire CanMEDS framework. This review informs current theatre and drama initiatives led by medical faculty aiming to develop their undergraduate medical curricula.

Tags: Applied theatre, Applied drama, Undergraduate medical education

Introduction

Experiential education allows students to deepen their learning by directly practicing their new knowledge. For medical students, experiential education encourages them to reflect and practice different clinical scenarios they will encounter as a physician. (1,2) Experiential learning in medical curricula is often centred around simulation-based learning and clinical skills training. (1) Overall, experiential education has learners consolidate their learning and test their new knowledge or skillsets in a consequence-free space; helping to develop their critical thinking skills. Ultimately, this should enable them to make good clinical decisions and provide the best care for their patients.

Applied theatre is the use of a theatrical performance, such as having students watch a play, as an experiential educational tool to promote change. (3,4) Relatedly, applied drama refers to learners participating in drama games such as improvisation or role-playing exercises for educational purposes; however, it is important to note that the terms drama and theatre are often used interchangeably in the literature. (4) A debrief commonly follows applied theatre or drama exercises so participants can reflect on how the exercises connect to their previous and new knowledge or experiences. (5,6)

Previous literature demonstrates the positive emotional and professional benefits of applied theatre in medical education. (7,8) Due to the diversity of the field, various medical institutions have taken unique approaches to integrating theatre within their curricula. For example, the University of California in Los Angeles developed an educational initiative that explores palliative care through Wit, a play sharing the final moments of Dr. Vivian Bearing who suffered from metastatic ovarian cancer. The performance of Wit is followed by a discussion regarding the play’s themes. (9) The play Wit has also been used for students to explore compassion and empathy in an introductory clinical practice course at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. (10) However, currently there is no compilation of applied drama programs to understand the overall educational and personal impacts of theatre for undergraduate medical trainees. The aim of this review is to gain a broad understanding of how drama and theatre are currently being used at different medical schools.

Methods

To ‘set the stage’ of the current literature surrounding applied theatre and undergraduate medical education, a scoping review was conducted A scoping review provided the opportunity to identify and evaluate the fairly unexplored literature pertaining to applied theatre in undergraduate medical education. (11–13) The five steps outlined by Arksey and O’Malley were consulted to help researchers collect, organize, and analyze the data from the various studies found in this literature search. (11)

Ethics

Ethics approval was not required for this research, as only existing published literature was reviewed.

Stage One: Identifying the Research Question

The research question for this project was: how have applied theatre and drama been used as educational initiatives in medical schools across Canada and the United States (USA)?

This review was directed at Canadian literature, as the intent was for Canadian faculty to understand how theatre is currently being incorporated into schools with similar learning objectives, resources, and student populations; enabling them to upon these initiatives to include theatre or drama in their medical curricula. Given the close contact and frequent collaborations with the USA, publications from American institutions were also included.

Stage Two: Identifying Relevant Studies

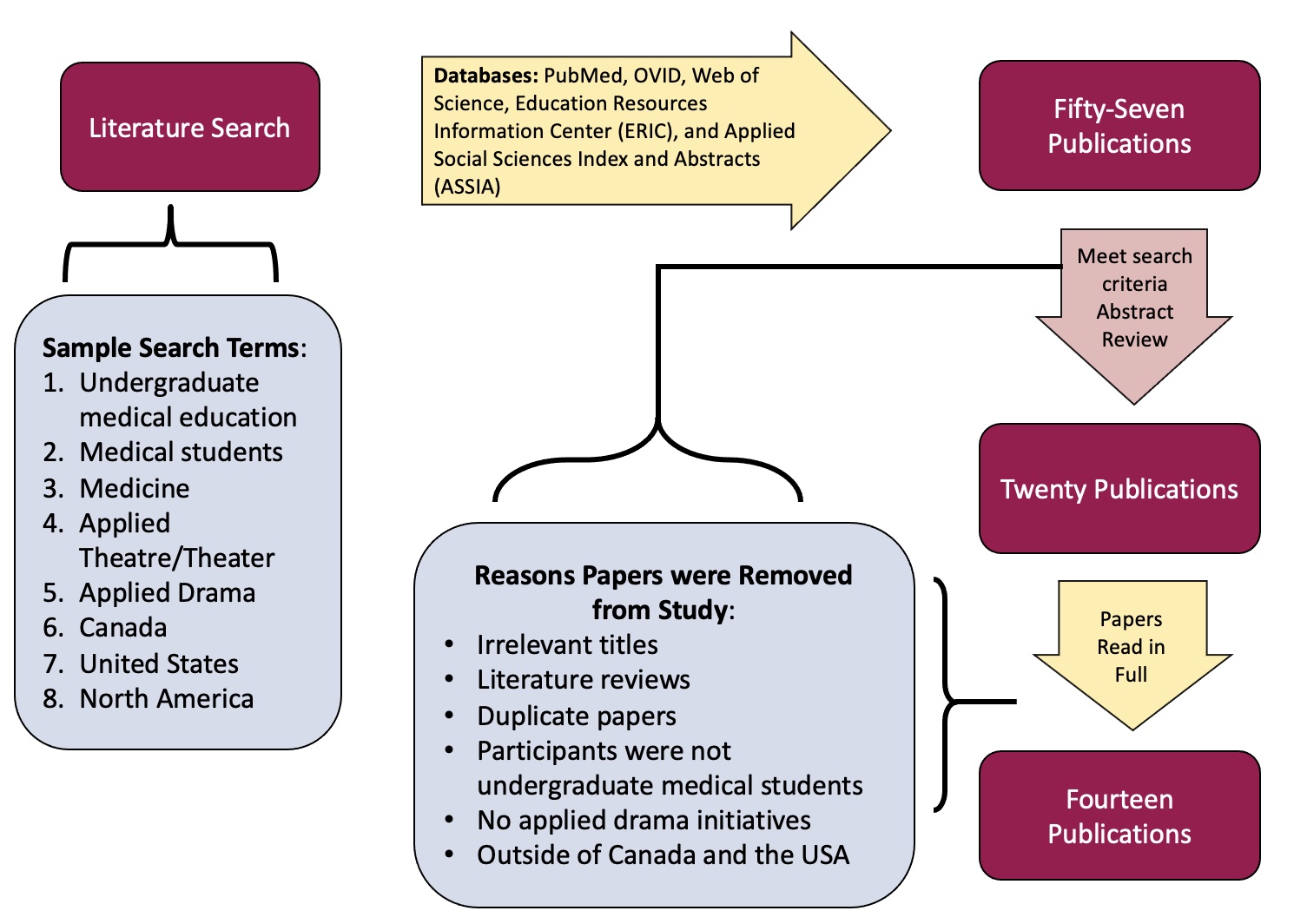

Various science and humanities databases were consulted to get a wide perspective of the current work surrounding theatre activities for medical students. These databases were: PubMed, OVID, Web of Science, Education Resources Information Center, and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. . A search strategy was developed in collaboration with the entire research team; a librarian was consulted for feedback on the search criteria. The search terms employed across all databases are listed in Figure 1. Only peer-reviewed articles were included to help ensure methodological oversight of the selected journal articles.

Stage Three: Study Selection

Strict inclusion criteria were employed to ensure the applicability of all included articles. Only studies that specifically discussed an applied theatre or drama initiative, involved undergraduate medical learners, and had connections to Canada and the USA were included in this review; all other research was excluded from this study. As the field of applied theatre and drama in medical education is small, no limits were placed on study publication dates. Only studies published in the research team’s first language were included to ensure appropriately interpretation of the studies.

The search results were then filtered based on their connections to the research question and if they clearly met the search criteria from their titles and abstracts. Duplicate articles were removed by BKJ. Relevant articles were then read in full by both researchers (BKJ and HJ) to ensure they met all aspects of the search criteria and the research question; the final selected papers were then analyzed (Figure 1).

Step Four: Charting the Data

Data from the papers was extracted in a table that listed the: study title, year of publication, a brief study description, the study location, and respective citation to organize all papers (Table 1). All included articles were published in peer-reviewed journals.

Step Five: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

To qualitatively analyze the data from the included papers, conventional content analysis was chosen to provide in-depth perspectives on the authors’ experiences and opinions of drama in undergraduate medical education. Given the variations on how applied theatre can be used as educational methods, inductive content analysis provided a high degree of flexibility for researchers to collate the categories and nuances from the different studies. (14,15) The included papers were read once in full before any coding occurred to jot field notes in order to start understanding their described phenomena. After the first review, initial coding was done by BKJ, selecting clear descriptions, comments, and analogies from the papers to minimize the risk of data misinterpretation. All initial codes were then consulted by the entire research team to ensure that they reflected the authors’ messages and data. The codes were also organized to see how they connected to the seven factors of the CanMEDS framework: communicator, collaborator, leader, health advocate, scholar, professional, and medical expert. (16) The CanMEDS framework was chosen to guide qualitative analyses, as it is the “most widely accepted and applied physician competency framework in the world.” (16)

The data codes were then refined and grouped to generate the overarching categories of this review. The three categories were reviewed again by the entire research team (BKJ and HJ) to ensure they accurately reflected the study descriptions on how applied theatre facilitates learning for medical students, landing on the final categories of this scoping review. All coding was done with NVivo12 software.

Results

Throughout the databases, 57 search results were filtered based on their relevance to the research question. The search criteria were run three times in January 2019, March 2020, and June 2021. Twenty relevant articles were read in full by the entire research team. In total, 14 publications were included in this scoping review (Figure 1). The publication dates ranged from 2003 to 2018, with the majority of articles (n=8) being published after 2010. Two articles were from Canada, seven were from the USA, and five papers were either spread throughout Canada and the USA or had affiliations with these two countries. The study populations varied in size - some initiatives were located at one university while larger studies were composed of conference workshops or collaborations between multiple medical schools (Figure 1).

Types of Applied Theatre and Drama Initiatives:

While each theatrical initiative was different, they can be summarized into two groups: 1) applied theatre followed by educational activities (n=6) and 2) applied drama exercises (n=8). Authors described drama or theatre activities they had created, or how educators integrated previously established material, like the play Wit (9,10), into their medical curricula. These articles shared student and faculty experiences and learner receptions of their theatre initiatives through student reflections/sharing of their experiences (10,17,18), course evaluations (5,6,17,19), student and faculty feedback (20,21), and group discussions (9,22,23). Some authors shared how they used surveys without further description of items (10,24–26), others were specific in sharing that they used a combination of quantitative and qualitative survey questions (24–26), and some only included quantitative questions. (10) The utility and benefit of applied theatre and drama in undergraduate medical education were illustrated by three categories of communication, creative medical learning, and professional development.

Communication:

Communication refers to the verbal and non-verbal exchanges of information from physicians to patients as well as the collaboration between healthcare providers. (16) Overall, communication was referenced in all papers (n=14), highlighting the extensive role it plays in medicine. Generally, drama allowed medical students to focus on expressing their ideas and experiences to improve their communication skills (Table 1). Specifically, Hoffman, Utley, and Ciccarone created an elective where first year medical students used improvisation to understand their personal perceptions and interactions with each other which helped them develop “strong communication skills… [to become] an effective health provider.” (6) Improvisational theatre also improved medical students’ storytelling abilities, enhancing the clarity of their ideas in clinical presentations. (18–20,24) Additionally, role-playing exercises involved students playing different parts in a scene so they could practice various interactions with patients and colleagues. (20,23,25) These drama activities were well received by students; for example, Hammer et al. stated that students perceived their listening and communication skills to be stronger as a result of drama being included in the curriculum. (24) Overall, drama helped teach learners how to deconstruct a conversation or improved their articulation abilities to clearly convey relevant clinical information.

Non-verbal communication skills were also discussed in the articles. Examples of non-verbal communication methods mentioned throughout the studies included, body language, gestures, eye contact, non-verbal expressions, and personal awareness. (5,9,17,24) Drama exercises targeted towards non-verbal communication skills allowed learners to further understand how to read others’ body language, the implications of their behaviour, and how they could improve their own non-verbal interactions. The play Wit illustrated the humanistic sides of palliative care. Notably, medical students saw how they needed to non-verbally communicate to emotionally support their patients; something that is challenging to teach using traditional didactic methods as they often overlook the complexities of coping with illness. (9) Watching a play or participating in role playing exercises allowed students to experience their patients’ fears and challenges, gaining a deeper understanding of illness and how to better support their future patients. (9,10,19) Drama workshops centred around acknowledging the senses helped students improve their awareness of others’ emotions to provide more empathetic care. (5)

Altogether, applied drama and theatre provided learners with opportunities to unpack both verbal and non-verbal communication skills to improve their interprofessional dynamics between colleagues and patients. It is important to note that throughout the papers, there was more emphasis on teaching verbal communication skills in comparison to non-verbal skills.

Creative Medical Learning

Theatre provided students with unique ways to emotionally connect with their medical learning (Table 1). Watching various productions of real patient stories brought to life for students the trials and tribulations patients experience with illnesses. (17) Comparably, Wit was well received by 95% of students, with many stating that they were “emotionally moved” by the performance and that it helped them further understand compassion and empathy (humanistic medicine) as well as palliative care. (9) By watching a play, students were able to experience realistic difficult patient stories through the safety of a storyline, making it an effective teaching tool to introduce challenging topics. Wit covered the difficult realities surrounding cancer and palliative care. (9) Drama provided learners with the freedom to think critically and divergently by creating an accepting learning environment where students saw that there is not necessarily one correct way to analyze a case or make good clinical decisions as a physician. (21,24,26) Additionally, the immersion students felt within a storyline opened their eyes to different perspectives and how they can connect deeper with their emotions, skills they can carry throughout their medical education and careers. (17,26)

The importance of experiential education in medicine can be summarized by one student’s thoughts about how “it is so hard to imagine without experience.” (25) These articles shared the importance of students actively participating in class to translate their new medical knowledge and skills into clinical experiences. Some educators did not directly focus their drama exercises on healthcare, but rather encouraged students to make their own connections on the relations between applied drama and medicine. (5,21) Kelly et al. (5) showcased how:

Role-playing was also frequently used for students to embody different characters or personas, often to replicate the patient-physician dynamic. (5,19,20,25) Medical students can often feel intimidated or unsure with how to proceed through challenging clinical scenarios, and playing the role of a clinician allowed learners to practice their clinical counselling skills in the security of drama. Students playing multiple characters were also excellent opportunities for learners to broaden their perspective of a scenario to understand what other ‘characters’ are feeling. Overall, theatre promotes the “retention and synthesis of new knowledge,” which aids students in becoming highly skilled, compassionate, and empathetic clinicians. (20)

Personal Development:

Personal development refers to a students’ ability for self-awareness and ability to improve their potential in both their professional and personal selves. Empathy was one of the most highly discussed skills educators felt was essential for students to be proficient in after medical school. Many teachers turned to theatre to facilitate empathy teachings and discussions for their students (n=9). (5,9,10,18,20,21,23–26) Consistently, drama and theatre exercises encouraged learners to care about a story and its characters. This provided insights to medical students in starting to understand patient-physician relationships, as well as how they could enhance their capacities to support others. (10,21)

Compassion was also widely discussed with respect to encouraging learners to reflect upon recognizing others’ pain and how they could help. (10,17,18,23) Experiencing Dr. Bearing’s cancer journey in Wit, medical students felt that this play gave them “a strong foundation for delivery of compassionate care in difficult situations” and how the arts can help keep patient stories at the forefront of their undergraduate medical training and future careers. (10) Playback theatre is another form of improvisational theatre that promotes personal development in which an audience member shares a story that is then performed by the actors. Medical students could form “connections with the audience” to more efficiently recognize the reactions and feelings of others as well as reflect on the shared peer stories in Playback Theatre, key aspects of compassionate care. (18)

Introducing theatre to medical students also helped them to understand the importance of establishing a professional-personal balance. Throughout the articles, enjoyment (19,22), stress relief (18,19,22), and wellbeing (22) were all attributed to drama being used in medical education. The joys theatre brought to medical school encouraged students to take breaks from academics, which re-iterated the importance of creating a work-life balance.

Overall, theatre was positively received and it was encouraged to continue using it as part of undergraduate medical education. For example, 95% of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine’s students who completed an improvisation class agreed that “studying improv could make me a better doctor” and recommended this course to their peers. (19)

Discussion:

The papers included in this scoping review highlight the importance of applied drama and theatre being integrated within three components of the undergraduate medical curriculum: communication, creative medical education, and personal development. Together, these three categories encompass the entire CanMEDS framework to help make students medical experts (Figure 2). (16,27)

Specifically, the category of communication directly connects to the communicator and collaborator traits (Figure 2). (16) Medical students need to have strong verbal communication skills to clearly convey relevant clinical information or to educate their patients on their conditions and respective treatment plans. Applied drama provides students with ample opportunities to practice the skills they will need as a physician such as case addresses, clinical presentations, and navigating the patient-physician dynamic. (20,23,25) Physicians also need strong non-verbal communication skills to fully disclose their intended tone and also to pick-up on subtle non-verbal cues such as posture, tone, or hand gestures from their patients; skills Saldaña, Konos, and Naglie argue can be better taught through theatre in comparison to traditional teaching methods. (28–30) Theatre encourages awareness so trainees can understand how eye contact, body language, and facial expressions emphasize their intended messages and feelings, traits that will help medical students understand “how empathy is experienced and expressed.” (31) Finally, drama also permits students to connect or move with their bodies to understand the role their body, movements, and expressions play in communication. (5)

Further, applied drama helps create a safe learning environment where students can view healthcare issues through the eyes of an actor, as opposed to an actual clinician or patient. Drama exercises, notably improvisational theatre, also encourage students to take risks, think outside the box, and try new ideas to improve their practice. (32) Medical learners can refine their knowledge and work to become scholars and medical experts by acting out the new concepts they have learned in class. In doing so, they can identify their current strengths and areas of improvement to maximize their study revisions (Figure 2). (16)

The interactive and reflective nature of theatre and drama also encourages personal development in learners. The CanMEDS framework focuses on how physicians are to be healthcare leaders, a trait which connects to strong medical education and communication skills. (16,27) Theatre and drama as experiential education allow students to expand their didactic healthcare knowledge and clinical skills, which they can carry forward in leadership positions (Figure 2). Notably, plays (applied theatre) allow undergraduate medical students to appreciate various perspectives of a scene. This can help them emotionally connect (29) and reflect on these stories, such as how would they feel being in that patient’s position or how they would have resolved character conflicts. (9,10,17,26) Consistently showing patients’ perspectives and experiences keeps them at the forefront of medical education. Patient stories also illustrate the importance of altruism in healthcare and leadership —something challenging to achieve in traditional course materials because patients can get lost in the facts and statistics that students learn in lectures (Figure 2).

Applied theatre and drama encourage student reflections and a critical consciousness to help learners guide their self-improvements. Debriefing and discussing activities or drawing connections between drama and medicine helped learners develop critical reflection skills that they can use and continue refining throughout their professional careers. Improvisational theatre also encouraged students to think quickly and translate their thoughts efficiently to help improve medical learners’ adaptability for their medical careers. The playful nature of theatre creates a fun and enjoyable learning space that promotes student participation. Partaking in therapeutic activities, like drama, encourages personal wellbeing and promotes health advocacy, therefore providing a potential solution to combatting the major issue of student burnout (Figure 2). (16,33)

Altogether, this paper showcases the various ways drama can help trainees become medical experts (Figure 2). While some Canadian and American medical schools have integrated theatre into their curriculums, overall theatre and drama unfortunately remain underutilized in curricula to facilitate medical learning. Therefore, more considerations for how applied theatre and drama can be integrated into medical education are needed to better educate and support medical students. It is hoped that this review will help undergraduate medical faculty realize the potential and understand how theatre can improve curricula.

Limitations:

Purposefully, the research question for this project was tailored to specifically evaluate current drama and theatre educational initiatives in medical school in Canada and the USA in peer reviewed journals. Therefore, minimal publications (n=14) were included in this review. A lack of literature makes it challenging to thoroughly analyze the depths of how theatre can enhance medical education and may also hinder the generalizability of the results in this scoping review. Another limitation is that this review only included articles in English; this could impede the generalizability of these results to all Canadian universities as some schools are French-English bilingual or only instruct in French.

Future Research:

Given the benefits of applied theatre and drama within undergraduate medical education, additional research to further understand the impacts of theatre in other health professions' education programs, such as postgraduate medical training or nursing, should be carried out. A systematic review on applied theatre is also recommended as a future research project , so as to have a deeper global perspective on how it is being used in undergraduate medical education across the world . Additionally, the study period for the majority of papers in the present review were quite short.; educational theatre initiatives largely took place over an academic year or a semester. Therefore, more research on the long-term influences, such as throughout students’ entire medical degree, of applied drama education for medical students is recommended. Additionally, with the difficulties in educating students during the Coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic, and now the progressive safe return to the classroom, one wonders if or how theatre has been used in medical education in response to COVID-19.

Conclusions:

Applied theatre and drama are unique educational tools that encourages creative medical learning, communication, and personal development for undergraduate medical students. The innovations and flexibilities that drama and theatre provide facilitate a diversity of experiential exercises that overlap with all aspects of the CanMEDS framework. (16) The utility and merit of theatre and drama in medical school should be further explored to improve current curricula so that trainees can provide the best care to their future patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada for granting us permission to discuss and reproduce the CanMEDS framework in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

We, the authors, declare no conflicts of interest associated with this research

References

- Kallail KJ, Shaw P, Hughes T, Berardo B. Enriching Medical Student Learning Experiences. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020 Jan 23;7:238212052090216. DOI:10.1177/2382120520902160

- Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: Transforming theory into practice. Med Teach. 2012 Feb;34(2):161–4. DOI:10.3109/0142159X.2012.643264

- Etherton M, Prentki T. Drama for change? Prove it! Impact assessment in applied theatre. Res Drama Educ J Appl Theatr Perform. 2006 Jun;11(2):139–55. DOI:10.1080/13569780600670718

- Obermueller J. Applied Theatre: History, Practice, and Place in American Higher Education. Theses and Dissertations. 2013. DOI:https://doi.org/10.25772/Y9JK-TJ19

- Kelly M, Nixon L, Broadfoot K, Hofmeister M, Dornan T. Drama to promote non-verbal communication skills. Clin Teach. 2019;16(2):108–13. DOI:10.1111/tct.12791

- Hoffman A, Utley B, Ciccarone D. Improving medical student communication skills through improvisational theatre. Med Educ. 2008 May;42(5):537–8. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03077.x

- Salam T, Collins M, Baker AM. All the world’s a stage: Integrating theater and medicine for interprofessional team building in physician and nurse residency programs. Ochsner J. 2012 Dec;12(4):359–62.

- Keskinis C, Bafitis V, Karailidou P, Pagonidou C, Pantelidis P, Rampotas A, et al. The use of theatre in medical education in the emergency cases school: an appealing and widely accessible way of learning. Perspect Med Educ. 2017 Jun 1;6(3):199. DOI:10.1007/S40037-017-0350-4

- Lorenz KA, Steckart MJ, Rosenfeld KE. End-of-Life Education Using the Dramatic Arts: The Wit Educational Initiative. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):481–6. DOI:10.1097/00001888-200405000-00020

- Deloney LA, Graham CJ. Developments: Wit: Using Drama to Teach First-Year Medical Students about Empathy and Compassion. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(4):247–51. DOI:10.1207/S15328015TLM1504_06

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005 Feb;8(1):19–32. DOI:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 Sep 20;5(1):69. DOI:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun 1;26(2):91–108. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687

- White MD, Marsh EE. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Libr Trends. 2006;55(1):22–45. DOI:10.1353/lib.2006.0053

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada: CanMEDS Framework [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e Available From:http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e

- Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Herwaldt LA. In their own words: Presenting the patient’s perspective using research-based theatre. Med Educ. 2005 Jun;39(6):622–31. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02181.x

- Salas R, Steele K, Lin A, Loe C, Gauna L, Jafar-Nejad P. Playback Theatre as a tool to enhance communication in medical education. Med Educ Online. 2013;18:22622. DOI:10.3402/meo.v18i0.22622

- Watson K. Perspective: Serious play: Teaching medical skills with improvisational theater techniques. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1260–5. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822cf858

- Ballon BC, Silver I, Fidler D. Headspace theater: An innovative method for experiential learning of psychiatric symptomatology using modified role-playing and improvisational theater techniques. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(5):380–7. DOI:10.1176/appi.ap.31.5.380

- Reilly JM, Trial J, Piver DE, Schaff PB. Using Theater to Increase Empathy Training in Medical Students. J Learn through Arts A Res J Arts Integr Sch Communities. 2012 Mar 2;8(1). DOI:10.21977/d9812646

- Nagji A, Brett-MacLean P, Breault L. Exploring the Benefits of an Optional Theatre Module on Medical Student Well-Being. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(3):201–6. DOI:10.1080/10401334.2013.801774

- Shapiro J, Hunt L. All the world’s a stage: The use of theatrical performance in medical education. Med Educ. 2003;37(10):922–7. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01634.x

- Hammer RR, Rian JD, Gregory JK, Bostwick JM, Birk CB, Chalfant L, et al. Telling the Patient’s Story: Using theatre training to improve case presentation skills. Med Humanit. 2011 Jun;37(1):18–22. DOI:10.1136/jmh.2010.006429

- Skye EP, Wagenschutz H, Steiger JA, Kumagai AK. Use of Interactive Theater and Role Play to Develop Medical Students’ Skills in Breaking Bad News. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(4):704–8. DOI:10.1007/s13187-014-0641-y

- D’Alessandro PR, Frager G. Theatre: An innovative teaching tool integrated into core undergraduate medical curriculum. Arts Heal. 2014;6(3):191–204. DOI:10.1080/17533015.2013.822398

- VanDewark K. CanMEDS Physician Health Guide: A Practical Handbook for Physician Health and Well-being. Univ Toronto Med J. 2010;87(3):125. DOI:10.5015/utmj.v87i3.1262

- Saldaña J. Ethnotheatre: Research from Page to Stage. Routledge; 2016. DOI:10.4324/9781315428932

- Saldaña J. Dramatizing Data: A Primer. Qual Inq. 2003 Jun 29;9(2):218–36. DOI:10.1177/1077800402250932

- Kontos PC, Naglie G. Expressions of personhood in Alzheimer’s: Moving from ethnographic text to performing ethnography. Qual Res. 2006 Nov 7;6(3):301–17. DOI:10.1177/1468794106065005

- Case GA, Brauner DJ. Perspective: The doctor as performer: A proposal for change based on a performance studies paradigm. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):159–63. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0B013E3181C427EB

- Felsman P, Gunawardena S, Seifert CM. Improv experience promotes divergent thinking, uncertainty tolerance, and affective well-being. Think Ski Creat. 2020 Mar 1;35:100632. DOI:10.1016/J.TSC.2020.100632

- Fares J, Al Tabosh H, Saadeddin Z, El Mouhayyar C, Aridi H. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016 Feb 1;8(2):75–81. DOI:10.4103/1947-2714.177299

| Table 1: A Summary of the Fourteen Papers Included in this Scoping Review. | Title | Publication Year | Brief Study Description | Location | Citation |

| End-of-Life Education Using the Dramatic Arts: The Wit Educational Initiative | 2004 | Wit was performed for medical students and other healthcare providers for palliative care education. Survey respondents shared how Wit helped their palliative care learning. *The Wit Initiative was shared throughout Canada and the USA. | Author Affiliations: California, USA | Lorenz KA, Steckart MJ, Rosenfeld KE. End-of-life education using the dramatic arts: the Wit educational initiative. Academic Medicine. 2004 May 1;79(5):481-6. |

| Exploring the Benefits of an Optional Theatre Module on Medical Student Well-Being | 2013 | A theatre-based module focused on empathy was created for students. These sessions were fun for learners and facilitated relationship building between each other and promoted personal growth. | Alberta, Canada | Nagji A, Brett-MacLean P, Breault L. Exploring the benefits of an optional theatre module on medical student well-being. Teaching and learning in medicine. 2013 Jul 1;25(3):201-6. |

| Developments: Wit: using drama to teach first-year medical students about empathy and compassion. | 2003 | Wit was included in a module to teach empathy and compassion. Wit was performed for students after a pre-play lecture, followed by a discussion with faculty, the cast, and cancer survivors. This initiative emotionally moved students and promoted positive attitude changes in students’ empathy skills. | Arkansas, USA | Deloney LA, Graham CJ. Developments: Wit: Using drama to teach first-year medical students about empathy and compassion. Teaching and learning in medicine. 2003 Oct 1;15(4):247-51. |

| Headspace Theater: An Innovative Method for Experiential Learning of Psychiatric Symptomatology Using Modified Role-Playing and Improvisational Theater Techniques | 2007 | Headspace theater used role-playing to simulate psychiatric conditions in small groups. This research consulted improvisational drama experts to share their experiences with medical students in addition to a literature review. Headspace theater was positively received by learners to understand the patient experience. | Author Affiliations: Ontario, Canada

West Virginia, USA |

Ballon BC, Silver I, Fidler D. Headspace theater: an innovative method for experiential learning of psychiatric symptomatology using modified role-playing and improvisational theater techniques. Academic Psychiatry. 2007 Sep 1;31(5):380-7. |

| Drama to promote non‐verbal communication skills | 2018 | Drama exercises were used to teach and refine non-verbal communication skills for medical students. This workshop allowed participants to have more awareness of non-verbal communication skills to aid with trusting relationship development. | Author Affiliations: Alberta, Canada Colorado, USA

Belfast, United Kingdom |

Kelly M, Nixon L, Broadfoot K, Hofmeister M, Dornan T. Drama to promote non‐verbal communication skills. The clinical teacher. 2018 May 23. |

| Using Theater to Increase Empathy Training in Medical Students | 2012 | A drama workshop to help teach communication skills, professionalism, and cultural competency was created. The workshop included various drama games, reflective writing, and images. This curriculum received positive feedback for teaching empathy, although some students struggled to understand the purposes of this workshop. | USA

Author Affiliations: California, USA |

Reilly JM, Trial J, Piver DE, Schaff PB. Using Theater to Increase Empathy Training in Medical Students. Journal for Learning through the Arts. 2012;8(1):n1. |

| Perspective: Serious play: teaching medical skills with improvisational theater techniques. | 2011 | A medical improvisation seminar was offered to medical students to improve their communication and professionalism skills. Students appreciated how the seminar promoted creativity and how they could immerse themselves into the exercises to improve their communication skills. | Illinois, USA | Watson K. Perspective: Serious play: teaching medical skills with improvisational theater techniques. Academic Medicine. 2011 Oct 1;86(10):1260-5. |

| Use of interactive theater and role play to develop medical students' skills in breaking bad news. | 2014 | An interactive drama class was centred around improving student skills of breaking bad news to patients. Actors played the patients and a small group of students had to practice breaking bad news to them. Students shared that they appreciated how this session promoted them to reflect up patient-physician communication and that the seminar was valuable. | Author Affiliations: Michigan, USA

District of Columbia, USA |

Skye EP, Wagenschutz H, Steiger JA, Kumagai AK. Use of interactive theater and role play to develop medical students’ skills in breaking bad news. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014 Dec 1;29(4):704-8. |

| Theatre: An innovative teaching tool integrated into core undergraduate medical curriculum | 2013 | A verbatim play, Ed's Story: The Dragon Chronicles tells the story of a 16-year-old boy who has cancer and unfortunately passed away based on interviews with Ed's loved ones and his journal. Students were required to watch the play and then participate in a discussion. Medical students felt that Ed’s Story should be mandatory in medical curricula. | Canada

Author Affiliations: Nova Scotia, Canada |

D'Alessandro PR, Frager G. Theatre: An innovative teaching tool integrated into core undergraduate medical curriculum. Arts & Health. 2014 Sep 2;6(3):191-204. |

| Playback Theatre as a tool to enhance communication in medical education | 2013 | Playback Theatre (PT) is improvisational theatre where performers act out real-life stories that the audience shares with them. PT performances were offered to medical students to share their stories and helped learners better communicate their emotions to others. | Texas, USA | Salas R, Steele K, Lin A, Loe C, Gauna L, Jafar-Nejad P. Playback Theatre as a tool to enhance communication in medical education. Medical education online. 2013 Jan 1;18(1):22622. |

| All the world's a stage: the use of theatrical performance in medical education | 2003 | Two one-actor plays on the patient experiences of living with AIDs and ovarian cancer were performed for medical students followed by a discussion. These performances helped students understand patient care and the importance of empathy in medicine. | California, USA | Shapiro J, Hunt L. All the world's a stage: the use of theatrical performance in medical education. Medical education. 2003 Oct;37(10):922-7. |

| Telling the Patient's Story: using theatre training to improve case presentation skills | 2011 | Drama training was integrated into medical education to help students refine their case presentation skills. The authors commented on the correlation between storytelling and communication skills in medical students. | Minnesota, USA | Hammer RR, Rian JD, Gregory JK, Bostwick JM, Birk CB, Chalfant L, Scanlon PD, Hall-Flavin DK. Telling the patient's story: using theatre training to improve case presentation skills. Medical humanities. 2011 Jun 1;37(1):18-22. |

| In their own words: presenting the patient’s perspective using research-based theatre | 2005 | The theatrical piece: In Their Own Words, was created by playwrights who have experienced illness. This piece was performed for first year medical students. The student's reflections indicated their increased awareness of hearing the patient perspective and the importance of providing patient-centred care. | Iowa, USA | Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Herwaldt LA. In their own words: presenting the patient's perspective using research‐based theatre. Medical education. 2005 Jun;39(6):622-31. |

| Improving medical student communication skills through improvisational theatre. | 2008 | First year medical students completed an elective centred around drama improvisation in medicine. These theatre exercises were centred around how students portray themselves, as well as their perceptions and interactions with others. Students appreciated the elective and its respective debrief to better understand the patient-physician dynamic. | Author Affiliation: California, USA | Hoffman A, Utley B, Ciccarone D. Improving medical student communication skills through improvisational theatre. Medical education. 2008 May;42(5):537. |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.