Original Research

Advance Care Directives: A Herzl Clinic Quality Improvement Project on Patients' perspectives

Alexandru Ilie1,

Adrienne Poitras2,

Zhou Fang2,

Keith J. Todd3,

Fanny Hersson-Edery3

Published online: November 2023

1Medical Student, McGill University Faculty of Medicine

2Residents at Herzl Clinic and the Department of Family Medicine, McGill University

3Herzl Clinic and the Department of Family Medicine, McGill University

Corresponding Author: Fanny Hersson-Edery, email: fanny.hersson-edery@mcgill.ca

DOI: 10.26443/mjm.v21i1.1036

Abstract

Background: Advance Care Planning (ACP) has benefits for patients and is often optimal when done in the primary care setting. Despite the development of multiple resources and tools to support ACP discussions at our Family Medicine Teaching Clinic, the initiation and documentation of Advance Care Directives (ACD) in patients’ medical files were low and resident physicians had perceived that patients were unwilling or unprepared for ACP discussions. The goal of this project was to understand the challenges and barriers that patients and their caregivers face in initiating and discussing ACD with their primary care team.

Methods: An online survey was conducted among 78 patients who are part of the Home Care program at the Herzl clinic. Participants were asked about the value placed on ACP and their preferences on various aspects surrounding the initiation of ACD discussions.

Results: 25 of 78 possible responses were received. This included survey responses from 6 patients, 13 caregivers, 4 family members and 2 physicians. Our results show that patients and their caregivers value Advance Care Planning discussions (>80%). Additionally, they endorse multiple benefits of ACP for themselves, their care teams and families. Patients and caregivers prefer that medical professionals initiate and facilitate the discussions (70-80%) and are open to receive educational material to prepare for these discussions (68%).

Conclusion: Patients in a frail population are willing and open to discuss advance care planning with their primary care team. Family Medicine teaching clinics can support patients’ desire to engage in ACP by providing access to education material and initiating these discussions.

Tags: Advance Care Planning, Advance Care Directives, Patients

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) includes the exploration of patient’s values, desires, and wishes regarding end-of-life care, such as precise level of care and goals of treatment, as well as the consideration of a surrogate medical decision maker in case of loss of capacity. ACP discussions and documentation are considered a best practice of medical care. Clearly identified and documented Advance Care Planning is a priority for the Ministry of Health in Quebec, Canada. La Loi concernant les soins de fin de vie recognizes the importance and primacy of a person’s clearly and freely expressed wishes regarding care, notably through the establishment of the system of Advance Care Directives (1).

Advance care planning has been shown to be beneficial for patients and their families. It helps ensure that the patient’s consent is respected should they be judged incapable of participating in treatment decisions. This allows patients to have better end-of-life care, focused on their expressed wishes with the goal of improving their quality of life (2). There are also clear benefits for patients’ family members, lessening the burden of the bereavement process, which can be accompanied by guilt, anxiety and depression if their beloved one’s wishes were felt to not be respected at the end of life (2).

Primary care is an optimal setting for discussing Advance Care Directives with patients. In multiple studies participants have stated that they prefer to have these conversations in an outpatient setting, with their primary care physician, or someone whom they already have an established relationship (3). This minimizes the urgent or life-sustaining treatment decisions that must be made by a physician who does not know the patient’s values and wishes (4).

Many studies have looked at effective interventions to improve Advance Care Planning discussions in the primary care setting (2,3,6). The most successful intervention is to pursue an interactive discussion, that often extends over multiple visits as the patient’s disease or life situation changes (2,3,6). Including the patient’s family in these discussions, if possible, can improve the patient’s end of life care and decrease anxiety regarding their family members’ wishes not being respected (3). Unfortunately, multiple studies have shown that ACP does not occur regularly nor frequently (3).

Herzl clinic is a McGill Family Medicine teaching unit mandated to train residents in the competencies outlined by the College of Family Physicians of Canada. One such competency is Advance Care Planning or planning for end-of-life decisions. (7). Herzl clinic trains about 23 residents per cohort and has about 50 residents combined between first and second-year residents, as well as third-year fellows. Herzl Clinic cares for over 30,000 patients of which approximately 80 are in the home care program due to their frailty. Residents follow two home care patients in their resident patient practice during the two years of their training program.

The Herzl Home Care program had previously developed several educational and clinical resources for residents, including two different forms to document Advance Care Directives. However, it was recognized that the Advance Care discussions and forms were infrequently or only partially documented among our home care patients’ charts.

A 2021 Quality Improvement study at Herzl, using survey and focus group data, explored barriers to ACP discussions amongst resident physicians (8). Barriers identified by residents included their perceived lack of education, opportunity and time during clinical visits, as well as a perception that patients were unwilling or unprepared for advance care discussions.

Literature looking at patients’ perspectives on ACP in the outpatient setting support that patients prefer having these discussions in the aforementioned setting (9). Most participants preferred earlier ACP, when patients are non-frail and are able to participate in these discussions themselves (9,10). An adult general practice population indicated their preference was to initiate the discussion themselves (9). Interestingly, our population did not often initiate end-of-life care discussion with residents (8). However, the literature indicates that there is a portion of the population who consider ACP very important and would prefer that their family physician initiates the discussion (9). Preference for their family doctor to initiate the discussion correlated to the importance they gave to ACP discussions. Other studies have suggested that other health professionals such as nurses are well placed to initiate ACP discussions (11).

This quality improvement (QI) project was developed to better understand our home care patients’ perspectives on initiation of ACP discussions.

Methods

Online survey

A nine-question online survey was developed to probe the patients’ perspectives on ACP in our home care setting. Caregivers and family members were invited to answer the questionnaire if the patient was unable to do so autonomously. The survey was administered and hosted on the Qualtrics platform by the Quality Assurance Team at the CIUSSS Centre-Ouest health authority in Montreal. Ethics review and approval was granted by the same team.

78 Home care patients were invited to participate. An email invitation was sent to the patients who had a contact email in the medical record. A paper version of the survey was sent to patients who did not have an email address. 2/25 surveys were completed on the paper version.

A follow up email was sent 2 weeks later. A final attempt at increasing participation included phone calls to potential participants.

The 9-item survey used a mix of multiple-choice answers and 5-point Likert scales. It was available from February 2022 through April 2022. The survey was not pre-tested, and no monetary incentive was offered to participants.

The survey defined the components of ACP and ACD (the ‘what’) and explored the value respondents placed on ACP (the ‘why’). The following questions explored the process of initiating ACP discussions (by whom, when, where, and how)

The project was carried out by Drs Adrienne Poitras and Zhou Fang, residents in the Department of Family Medicine, McGill and supervised by Dr Hersson-Edery and Dr Keith Todd. Support was provided by Alexandru Ilie.

Results

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

Survey response rates were 32% (25/78), among which 6 respondents are Herzl patients themselves. Barriers to completion of the survey included hearing and vision impairment, or declining cognitive function. The largest group of respondents were patients’ caregivers (13/25). Family members and physicians answered for the patients in 6/25.

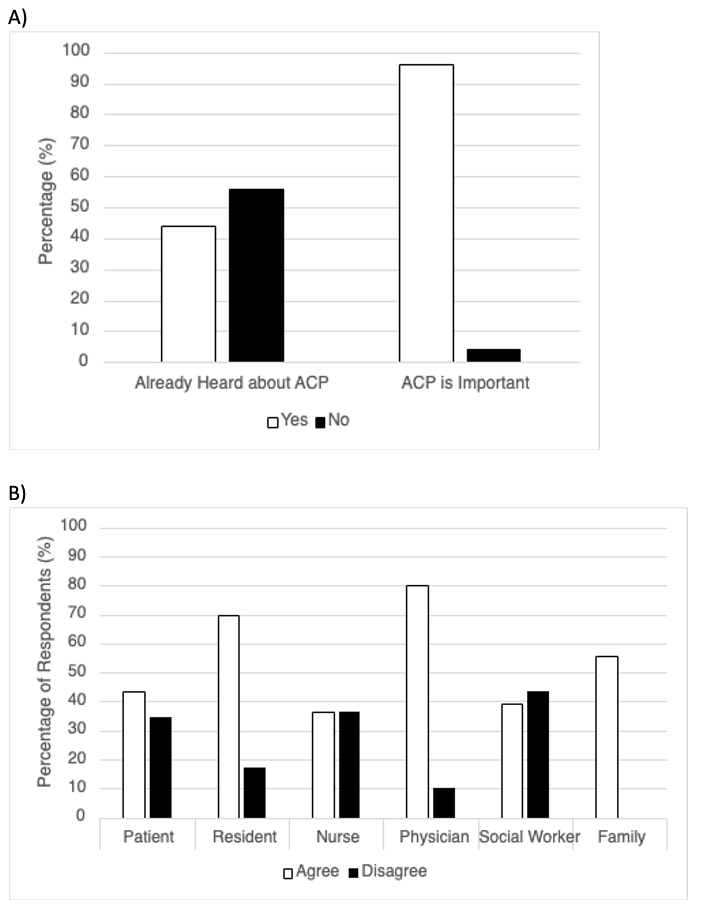

96% of responders agreed that it is important to discuss ACP with healthcare professionals, yet more than half (54%) had not heard about ACP prior to this survey (Fig. 1A), and less than 25% have discussed ACP at Herzl.

A majority of respondents (24/25) answered ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to the statement “It is important to discuss Advance Care Planning with a health professional” (Fig. 1A). Six of the remaining respondents agreed and one individual was neutral. The reasons for placing this value were multiple. Some reasons included a desire to understand the choices around end-of-life interventions, to prepare for end-of-life decisions, to pre-emptively make decisions to avoid burdening family members, to ensure that their wishes will be respected, and to ensure dignity at end of life. Most respondents (70%) indicated that ACD could help reduce disagreements between family members and health teams.

Timing and How ACP discussions should happen:

Respondents showed a clear preference towards retaining autonomy on when to initiating discussions. Another large proportion indicated they would want an invitation to discuss ACP when there is a change in their health status (16/25), whether there is a new diagnosis or deterioration in health status. Less than half of participants (10/25) indicated that they would want this discussion on a yearly basis, such as when a new resident physician took over care, or if they are healthy.

More than 50% of respondents indicated a preference for informal initiation of ACD during a previously scheduled medical visit, rather than a separately scheduled visit, an email or a phone invitation. Additionally, (15/25) 68% of respondents were open to receiving preparatory medical information on ACD or medical interventions such as CPR, intubation, or dialysis, either through paper or digital format, or for this information to be provided to their family or caregiver. A single participant indicated that they preferred to receive preparatory information via a website.

Who Should Discuss ACP

Participants expressed a stronger preference for the resident, staff physician or family member to bring up the ACP discussion, rather than a nurse or a social worker or themselves (Fig. 1B). 16 out of 25 respondents agreed or strongly agreed that a resident or staff physician should initiate the discussion.

Discussion

This quality improvement initiative adds important insights into how people think about advance care directives and their planning. Our results were somewhat surprising in that, although one would expect some knowledge of ACP amongst a frail population such as the one surveyed here, fewer than half had heard of ACP prior to the survey. Unlike a larger survey in Canada (12), our results are not focused on the term per se, since a definition was provided to ensure understanding. The work by Teixeira et al. (12), however, illustrated that many Canadians are engaging in these informal discussions with family members, which did not seem to be the case with our patients.

Our study confirms findings in the medical literature that patients prefer having physicians initiate discussions regarding end-of-life care in addition to facilitating the discussion when the patient brings it up or when there is a change is health status (9,10,11). The preference for involvement of a medical doctor may reflect a familiarity with these members of the care team since in our context since they are the professionals making the home care visits. However, it is quite likely that for other patients who were more familiar with other members of the health care team, such as a nurse or social worker, that these individuals would be the preferred contact person for these discussions (11).

The surprisingly small proportion of people who were aware of ACD and who had participated in discussions highlights the need for more patient education. This seems not to be unique to our population as survey administered across Canada found that only 16% of people were aware of the term and only 20% had a written advance care plan (12). Interestingly, the residents’ perception that patients, their caregivers, and their family members are reluctant to prepare and discuss end-of-life care in the outpatient setting (8) was not supported in our iterative follow-up quality improvement project. Our survey did reveal an openness by patients and families to receive educational material prior to discussions. This gives us clear opportunity and focus for changing patient awareness to facilitate more frequent ACP discussions. Patients and family members also indicated a preference for individual, in-person visits with their physician and family members, while there was little interest in group discussions on ACP. This also clarifies where we need to focus our implementation strategies.

Considering the limitations posed by the frailty and other possible barriers such as communication, auditory or cognitive difficulties, of our patient population we hope to extend this survey to the general older adult population at Herzl Clinic to see if their experience and perspectives on the initiation of Advance Care Planning and Directives differ.

Limitations of study

The low response rate of 32% was likely multifactorial. In addition to the fact that our Home Care patients form a frail population in which varying degrees of cognitive, language or hearing barriers are not uncommon, many do not have or use email, and some would have difficulty understanding how to access an online survey. Only 6 out of 25 respondents were the patients themselves and family members answered the survey in 4/25 surveys.

Due to these anticipated barriers, the authors followed up with phone calls and offered to administer the survey by phone, which increased our response rate considerably. Most of our respondents were caregivers (13/25), who despite knowing their care recipient well, do not necessarily have the same values and beliefs as their care recipient, and therefore may not always respond to the survey in the same way the patients would themselves. Indeed, caregivers did include their care recipient in answering the survey questions, when possible, but it is unclear how well the responses reflected the patients’ perceptions. We did not capture the prevalence of significant cognitive and sensory barriers to participating in this survey among our population.

In conclusion, this study advance our understanding of the challenges patients, caregivers, and family members in a frail Home Care population perceive in the initiation and discussion of Advance Care Directives with their physicians in the outpatient setting. Patients identified several areas of improvement that will be addressed in future iterations of this quality improvement project in order to improve the frequency and quality of Advance Care Planning discussions between Family Medicine residents or staff physicians, and their patients.

References

- Directives médicales anticipées : Loi concernant les soins de fin de vie. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2018 Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, 2018 ISBN 978-2-550-82963-8 (Imprimé) ISBN 978-2-550-82964-5 (PDF) https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2019/19-828-03F.pdf http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/showdoc/cs/s-32.0001

- Wickersham E, Gowin M et al. Improving the Adoption of Advance Directives in Primary Care Practices. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. March 2019, 32 (2) 168-179.

- O’Sullivan R, Mailo K. et al. Advance directives. Canadian Family Physician. Apr 2015, 61 (4) 353-356.

- Coppola KM, Ditto PH et al. Accuracy of Primary Care and Hospital-Based Physicians' Predictions of Elderly Outpatients' Treatment Preferences With and Without Advance Directives. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(3):431-440.

- Kononovas K, McGee A (2017) The benefits and barriers of ensuring patients have advance care planning. Nursing Times; 113: 1, 41-44.

- Spoelhof GD, Elliott B. Implementing Advance Directives in Office Practice. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Mar 1;85(5):461-466.

- Crichton T, Schultz K, Lawrence K, Donoff M, Laughlin T, Brailovsky C, Bethune C, van der Goes T, Dhillon K, Pélissier-Simard L, Ross S, Hawrylyshyn S, Potter M. Assessment Objectives for Certification in Family Medicine. Mississauga, ON: College of FamilyPhysicians of Canada; 2020

- Eladas, et al. Advance Care Directives : A Herzl ClinicQuality Improvement Project (McGill J of Medicine) In Press

- O'Sullivan R, Mailo K, Angeles R, Agarwal G. Advance directives: survey of primary care patients. Can Fam Physician. 2015 Apr;61(4):353-6. PMID: 25873704; PMCID: PMC4396762.

- Lin CP, Peng JK, Chen PJ, Huang HL, Hsu SH, Cheng SY. Preferences on the Timing of Initiating Advance Care Planning and Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatment between Terminally-Ill Cancer Patients and Their Main Family Caregivers: A Prospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7954. Published 2020 Oct 29. doi:10.3390/ijerph17217954

- Kononovas K, McGee A (2017) The benefits and barriers of ensuring patients have advance care planning. Nursing Times; 113: 1, 41-44.

- Teixeira AA, Hanvey L,Tayler C, Barwich D, Baxter S, Heyland DK. 2015. What do Canadians think of Advance Care Planning? Results of an online opinion poll. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 5:40-47.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.